Father Atanas (English version)

- Leontius Project

- Nov 23, 2020

- 10 min read

In the words of Benjamin Franklin "If you would not be forgotten as soon as you are dead, either write something worth reading or do something worth writing". To say that my great-grandfather, orthodox priest Atanas Arginov, did both those things can not be denied. In recent decades his legacy has resurfaced in the form of an hand-written autobiography that details his fascinating life, and the appalling atrocities experienced by his family during the Balkan Wars. More importantly though, the value of his work is found in the small pieces of wisdom throughout his narrative; wisdom based on values such as forgiveness, gratitude and faith.

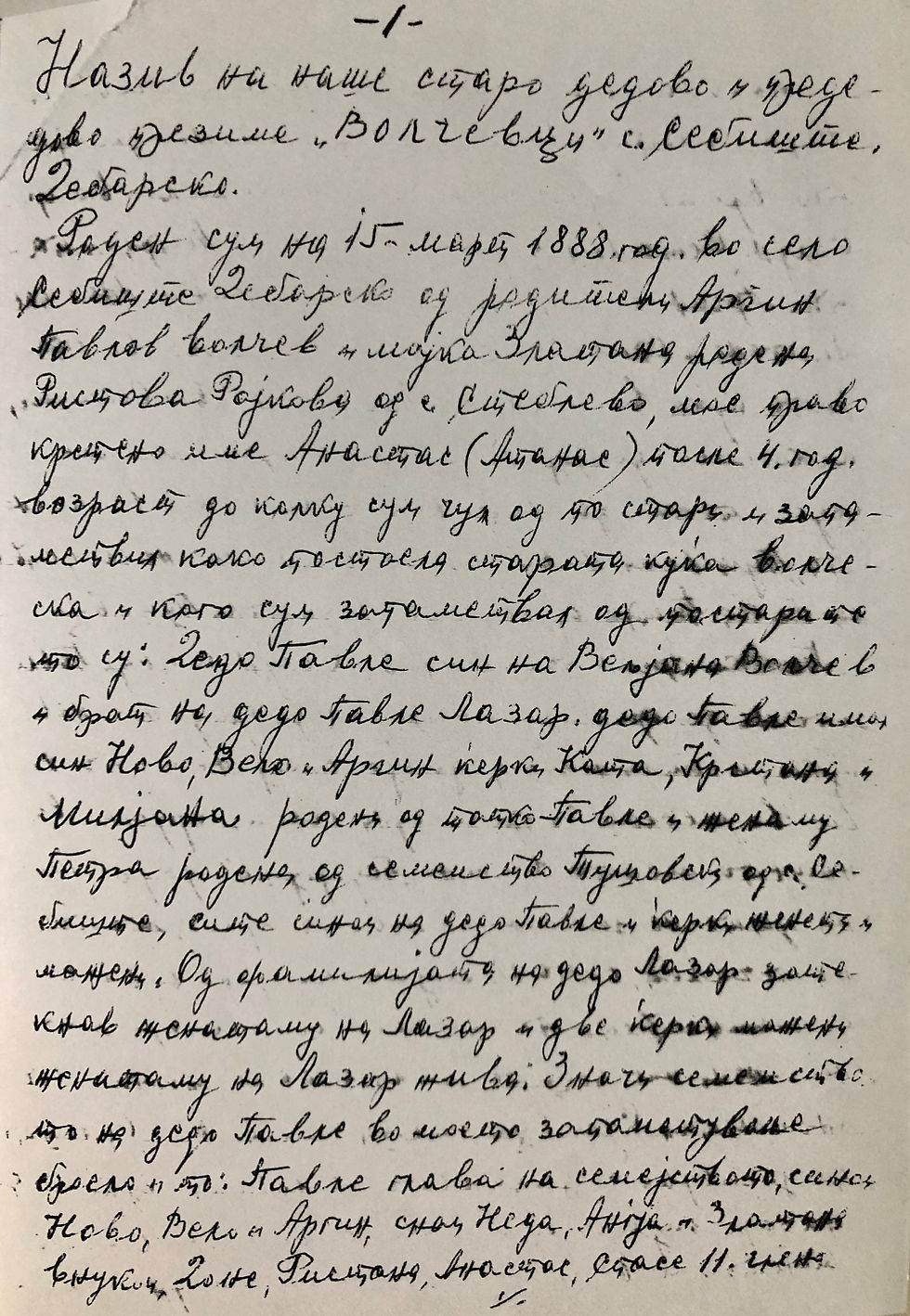

The story begins with the birth of Anastas Volčev on 15 March 1888 in the village of Sebište, Debarsko, which today falls within an area called Golo Brdo (Golloborda in Albanian), just inside the Albanian border with Macedonia. According to the census conducted by Vasil Kančov in 1900, the village had a mixed population of 360 Christians and 400 Muslims, all of whom spoke Macedonian. His earliest memory was as a four year old boy living in the house of his grandfather Pavle. The members of the household also included his grandmother Petra (nee Tušov), parents Argin and Zlatana (nee Rajkov from the village Steblevo), siblings Ristana and Spase, his uncle Novo with wife Neda (who were childless) and uncle Velo and wife Angjia with their son Done.

In the years that followed, his uncles Novo and Velo moved to Solun (Thessaloniki, Greece) with their families. His father Argin followed, and was "employed as a contractor for an Austrian company that had bought the railway line from Solun to Ristovac from a Turkish company". Research indicates that this company was most likely Deutsche Bank that was given a concession by the Ottoman Sublime Porte to build the railway in 1890. Argin was responsible for the section of the track maintenance from Solun to Demir Kapija. The line still exists along the banks of the Vardar river.

The family home in Sebište was run down and delapitated so Pavle and Argin decided to build a new home on land inherited by Petra from the Tušovski family. Pavle died before the new build had commenced, and with Argin working in Solun, they commissioned Sulo Odža “bivši kmet” of the village to oversee the construction. He hired a man called Zuber from the nearby village of Zabzun as the foreman, and other workers from the village of Lesnicane. Argin continued to send funds to pay the workers and the house was eventually completed. In the new house were born Anastas' last three siblings; Stojan, Nevena and Lazar.

In 1899, Argin took Anastas with him to Solun and enrolled him in a four-year program at the Sts Cyril and Methodius Bulgarian Men’s High School. He diligently attended the first three years until 1903 when the school briefly closed due to the Ilinden Uprising. Therefore, he exited the program without the final year of education. During those years, he travelled between Solun and Sebište on seven separate occasions, making his way by travelling with groups of horse traders. Each trip from Solun to Sebište took seven days. After his schooling, Argin took Anastas to work alongside him, documenting listings of his workers and managing their pay.

In 1907, there was a major flood of the Vardar River which covered large sections of the railway line. Argin was sent with a larger group of workers to assist with emergency operations and pumps were brought in to remove water from the tracks. They also helped passengers transfer between trains via bridges made of planks. From the exhaustion and hard physical labour, Argin caught pneumonia and passed away at the home of Novo in Solun. He was only 48 years old.

Returning to Sebište as the new head of the family, he married Ristana Budinov from the village of Klenje on 25 Jan 1909. His sister, also called Ristana, married Pano Filoka (also from Klenje) the week before. Members of these families still live in Klenje and other parts of Albania with the albanianised surnames Budini and Filoqi.

Shortly after his first child Arsa was born in 1911, the people of Sebište started a search for a new priest since the old priest Prendov had passed away. At first, they sought out one of the sons of the old priest to take his place, but he wasn’t interested in taking the role, so they went to beg Anastas. He was chosen because, as a young boy, he would often help the old priest whenever his other assistants weren’t available. He agreed, and started to perform basic religious duties across 35 households in Sebište, as well as teach at the village primary school.

"We are mountain people, we sow our seeds late and without the wheat fully grown we pick it early, mill it into flour and use it to bake bread."

In 1912, he travelled with some high-profile villagers to Debar to appear before the Debarsko-Kičevski Kozma (Archbishop) . When they arrived at his office, they were told that he had gone to Constantinople to meet the Bulgarian Ekzarh Josif. They then asked to see his Deputy, Episkop Nišavski Ilarion, explaining that Anastas was there to be put forward as a candidate to be officially ordained into the priesthood, with the villagers as his delegates. The main problem was that he was only 24 years old. The regulations stated that men were only able to join the priesthood once they reached 30 years of age. The delegates explained, "we are mountain people, we sow our seeds late and without the wheat fully grown we pick it early, mill it into flour and use it to bake bread. Therefore, he too, though young, will be able to take on the role". Not only is this a testament to the faith they had in Anastas, but also insight into the humble life they lived in those mountain villages.

The Episkop agreed to write to the Kozma in Constantinople and seek his permission. The news later arrived that he could progress to be ordained. On 29 April 1912 Anastas went to Debar and was initiated as a deacon. The next day he commenced his six weeks of study at the monastery Sv. Jovan Bigorski together with another young priest from the village of Rajčica Debarsko. By Petrovden, they were both serving in their respective parishes, he in Rajčica and Anastas in Sebište.

In October 1912 the First Balkan War broke out resulting in the Balkan nations uniting to overthrow the Ottoman Empire. The Balkan armies then occupied the remaining lands with the whole of today’s Macedonia and Albania to Drach being occupied by the Serbian Army. After a brief time, the Balkan allies commenced discussions around the Macedonian territory with Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia all wanting a piece of the pie. In 1913 the Second Balkan War broke out between Bulgaria and Serbia.

With Sebište being occupied by the Serbian army, Albanian rebels started to make gains on the Serbs. The Serbian army was driven out of the village and the Christians of the village were told to follow them in order to save their lives. Many of the village rebels gathered in Anastas' house, with his brother Spase and some fellow villagers already hiding in other surrounding villages after anticipating danger. On 11 September 1913, he and the rest of his family were abruptly forced to leave the home. They travelled to Klenje to stay with relatives but that same evening his mother Zlatana, wife Ristana and the other children travelled back to Sebište. His brother Spase remained in the mountains with his peers and Anastas stayed hiding at a relative's house since as the village orthodox priest he was most in danger. That night two known Muslims from Sebište came to Klenje to find Anastas and bring him back to the village. He didn’t oblige and so they left him. If he had have gone with them God only knows what would have happened to him.

Back in Sebište his mother, wife, siblings and daughter hid in the house of Arsan Gina because they were scared of the people that they had found gathered at their house. When they woke the next morning, the rebels sent a man to call his mother to come and open up the house so they could lock up those villagers they had collected through the night in their cellar. They then called for his wife with the children to also be brought to the house. They too were locked inside; Zlatana, Ristana, Stojan, Lazar, Nevena and Arsa.

After a while, Sulo Odža ordered Zlatana to go and find her sons, being Anastas and Spase, and if she didn’t bring them back, he would burn the house down. Zlatana yelled back at him that given he built the house, then he could burn it down! With not a moment to spare, Zlatana set out to find her sons in Klenje. When she arrived, she found Anastas in the house he had been hiding in the night before. She told him the order of events and everything the rebels had told her, including that if she didn’t bring him back, they would burn the house down. No one really cared about the house, but inside were his wife, daughter and young siblings and he had to make every effort to save their lives.

On their return to Sebište they decided not to take the main road but went via Valesino Pole, one of their fields on the Sebište/Klenje border. From there they could see the village and their house. At that point, they could see a large flame in the far distance coming from their house; it was already on fire.

Anastas' wife, my great grandmother Ristana, was the eyewitness to the terrifying atrocities against the villagers on the that day. The rebels had selected those they wanted to torture and kill and locked them in the cellar of their house. Anastas' brother Stojan was included in that group. Ristana and the other children were upstairs inside the house and, watching from above, she witnessed the rebels take the men out of the cellar one by one, giving them orders of what to do next. Some they let go, some they bashed and some they tied up in pairs. Others they stripped naked and sent home as they did with Stojan. One of the rebels holding the men in the cellar gave way for Stojan to go up into the house with Ristana and the others, perhaps because the rebel (one of Sulo's sons) had remembered all the good that he had received from their household. They killed their sheep, boiled the meat for themselves and once they were done eating, they shot the men they had tied up. They were: Trpko Djoka, Trpko Kušta, Spase Kušta, Novo Gina, Srbin Pepa, Stamat Karakaska, Božin Gina and Arsan Gina.

The family were still inside the house when Jusuf and Alija Odža (sons of Sulo) set the house alight. Once he saw the house fill with smoke, Jusuf opened the door and told Ristana and the others to run. He swore that with God’s will the same would happen in Klenje as had happened there, then onwards to Steblevo and Jablanica! With that, Ristana, Stojan, Lazar, Nevena and Arsa ran to find refuge. Not knowing where to go or which road to take, and with the children small and barefoot, they finally arrived at Klenje.

The autobiography goes on to outline the madness and confusion that ensued over the following week as the rebels made gains on the territory. To summarise, Ristana, Stojan, Lazar, Nevena and Arsa reunited with Spase and the Budinov and Filoka families in Klenje, and were subsequently forced to escape to Golemovo, and then on to the village of Drenok. Anastas and Zlatana, unable to return to Klenje, sought refuge in Steblevo with the family of Zlatana's brothers Isak and Milenko Rajkov (Milenko was also a priest) and sister Petkana Spanec. Once Steblevo became occupied, the group attempted to go east towards Jablanica, but they were forced to retreat and climbed higher into the rugged Steblevo mountains. Finally, the Serbian army regained their territory from the Albanians and the family was reunited in Sebište at the house of Gjorgi Batala since their home had been destroyed by the fire.

By 1914, battle over the territory recommenced and a process of ethnic cleansing was carried out. Villages to the west were designated as being Muslim, those to the east as Christian, and a population exchange occurred. Anastas and his family were sent to the village of Konjari and given a house that once belonged to a Muslim by the name of Etem Čiče. During that period a Serbian census was commissioned for all the refugees in the area. That same commission resulted in the changing of his name from the Greek sounding Anastas to the more Slavic Atanas. His surname was also changed to Arginov after his late father Argin. His brothers Spase, Stojan and Lazar were also Arginov until some years later when it was changed to Pavlov (after their grandfather Pavle). This was based on the tradition in the Bitola region of taking the grandfather's name as one's surname. Spase was also the first man from their region to be recruited into the Serbian army on 20 March 1914.

They stayed in the Debar area for 21 months, after which they returned to Sebište on 1 June 1915. The Serbian army and government stayed until 30 November 1915, after which their land was occupied by Germany and its allies, leaving Albania with primary control. Once again, the same rebels returned and began harassing the family since Atanas had just begun preaching in Debar. They demanded that Zlatana give them the family’s only horse in exchange for them saving the lives of her family when they burned her house in 1913. Zlatana and Ristana tried to come up with a plan to guard the horse from being taken and they asked all over the village for advice. Some said to give it over to them while others said not to. They came across a muslim man called Kadri Karadža who was born in Sebište but now lived in Golem Ostrene (today Ostren i Madh). He told them not to give the rebels the horse and, envisaging further harassment, said that they should all go with Maloica, a woman from the Karadža household in Sebište, to his house in Golem Ostrene. He told them that they were welcome to stay at his house if they wished, so long as they didn’t give in to the rebels. Kadri must have known that the harassment was going to become more scathing to offer that sort of assistance. Atanas, a man of gratitude, wrote the following...

"That man, though a Turk, did us a great service and for that we all thank him. The next day when the rebels returned, they found neither horse nor human and, as I said, until now no man has ever done anything more thoughtful for us than that"

They chose not to stay in Golem Ostrene, but carried on through the night. Zlatana, Ristana, Jovanka (Spase's new wife), Stojan, Lazar, Nevena and Arsa, along with the horse, made the strenuous journey through the mountains to Drenok. They never returned to Sebište again. The family lived for the next 14 years in the Struga area with Atanas preaching in the villages of Jablanica, Dolno Belica, Labuništa and Podgorci. With his brothers already living and working in Trnovo-Magarevo near Bitola, Atanas took the position of parish priest in the nearby village of Capari where he would serve for 46 years until his retirement on 20 June 1966.

Beautiful story and well preserve history for future Macedonian generations. Congratulation, well done Adam.